Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a weekly column dedicated to doing exactly what it says in the header: shining a light on the some of the best and most relevant fiction of the aforementioned form.

Speculative fiction makes up maybe nine out of every ten texts I take it upon myself to dissect, but from time to time, I admit it: I like a little literary fiction. To wit, alongside The Book of Strange New Things by Michael Faber and The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell, one of the most exciting new releases of 2014 for me has to be Haruki Murakami’s next novel.

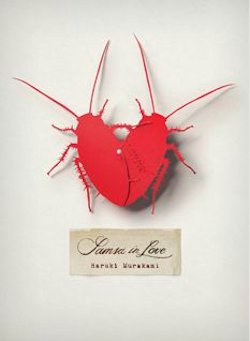

Random House has not yet set a date for it in the UK, but Knopf plan to publish Colorless Tsukuru and His Years of Pilgrimage in August, which is not so long off as it once was… so over the holidays, I got myself well and truly in the mood for Murakami’s new book by way of a short story in The New Yorker. As you’d expect, “Samsa in Love” is immediately surreal.

He woke to discover that he had undergone a metamorphosis. [He] had no idea where he was, or what he should do. All he knew was that he was now a human whose name was Gregor Samsa. And how did he know that? Perhaps someone had whispered it in his ear while he lay sleeping? But who had he been before he became Gregor Samsa? What had he been?

What indeed. Something other, evidently—and something weird, clearly—because Samsa is horrified by the softness and strangeness of his body:

Samsa looked down in dismay at his naked body. How ill-formed it was! Worse than ill-formed. It possessed no means of self-defence. Smooth white skin (covered by only a perfunctory amount of hair) with fragile blue blood vessels visible through it; a soft, unprotected belly; ludicrous, impossibly shaped genitals; gangly arms and legs (just two of each!); a scrawny, breakable neck; an enormous, misshapen head with a tangle of stiff hair on its crown; two absurd ears, jutting out like a pair of seashells. Was this thing really him? Could a body so preposterous, so easy to destroy (no shell for protection, no weapons for attack), survive in the world? Why hadn’t he been turned into a fish? Or a sunflower? A fish or a sunflower made sense. More sense, anyway, than this human being, Gregor Samsa.

Luckily, his rambling reverie is interrupted by the arrival of a “very little” locksmith; one come from the other side of a city in the midst of some unspecific but seemingly serious strife to fix the door of the room Samsa awoke in moments ago.

He does wonder why her task is so important… but only for a moment. In truth Murakami evidences little interest in that aspect of the narrative; instead he’s drawn inexorably towards the locksmith’s disability. She’s hunchbacked, as it happens:

Back bent, the young woman took the heavy black bag in her right hand and toiled up the stairs, much like a crawling insect. Samsa laboured after her, his hand on the railing. Her creeping gait aroused his sympathy—it reminded him of something.

Ultimately the locksmith arouses something more in Samsa than his sympathy, hence his sudden onset erection. He, however, has no idea what it means; she, when she sees it, deigns to explain it to him in his innocence. What follows is an awkward and often comical conversation during which our metamorphosed man learns about love—about why it might just be good to be human.

Serious readers will realise right away that “Samsa in Love” is inversion—a prequel or a sequel of sorts, it matters not—of Franz Kafka’s classic novel, The Metamorphosis. At bottom, it’s about a beetle transformed into a man rather than a man who becomes a beetle, and if the story alone isn’t worth writing home, its references render it relatively interesting.

In addition, its perspective is independently powerful:

He picked up a metal pot and poured coffee into a white ceramic cup. The pungent fragrance recalled something to him. It did not come directly, however; it arrived in stages. It was a strange feeling, as if he were recollecting the present from the future. As if time had somehow been split in two, so that memory and experience revolved within a closed cycle, each following the other.

In the strangeness of the mundane—in the day to day, observed as if by an alien—Murakami finally finds purchase, and piles upon it.

That said, what tends to make Murakami’s work resonate is the incremental accretion of meaning over the course of his bizarre narratives, and though there is room in the short story form for this building sense of significance, at times “Samsa in Love” can be seen to meander almost meaninglessly.

Better than it had been the basis of a full length book in which Murakami might have explored these ideas for more than a moment. ‘Samsa in Love’ simply seems crude in comparison to many of the author’s other efforts. If you haven’t read The Metamorphosis, I wouldn’t bother with it at all. If you have, prepare yourself for something strange, and sadly dissatisfying.

Though “Samsa in Love” is ultimately uplifting, it left me at least mostly cold. I certainly didn’t adore it, in much the same way I didn’t adore the three increasingly tedious volumes of IQ84—albeit for completely different reasons. But so it goes, I suppose.

I remain reasonably keen to read Colorless Tsukuru and His Years of Pilgrimage. I’ll be approaching it with tempered expectations, however. My hope is that Murakami’s idiosyncratic brand of fantasy can still charm me, though I dare say I’m afraid this dog may have had his day.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.